My gasp is a question

that my daughter answers: Yes, those were babies. And she wonders-- Where were they going? Five young possum and their mother, still among the forgotten shoes and plastic bags of 8th Street.

1 Comment

The thing about middle age is you see what’s coming for you.

3:17pm:

He smells of stale PE, she vibrates with story, and the news is talking of war and gasoline. She slides into the car, telling me already that she has decided to be weird and Sol has decided to be a they and can I please turn off the news. In the mirror I see a fight brewing in him, so I ask-- How was your day? He sighs: another day of hurts, but also of Jackie Robinson and trampoline classes and grasshoppers, and of wondering what it means to have depression. I tell my therapist that my soul is locked behind a door made of ancient wood and that the mahogany guards a snarl that is better off in darkness. That snarl wraps around shame and judgment and loneliness and inadequacy and terror and emptiness and exhaustion and meaningless, and if the door opens, I know I will enter. Because the door is also an invitation. That locked away place is dark and warm, and I fit, snuggled in the comfort of pain. Maybe the Cure plays, or maybe Patti Griffin, and maybe there is the densest down duvet I’ve ever wanted thrown over my old porch rocker offering warmth and heaviness and silence. And if I sit and tuck myself away here, I know I will not emerge. That snarl of feeling will gather around me, and it will squeeze, and I will struggle to breathe and beat on.

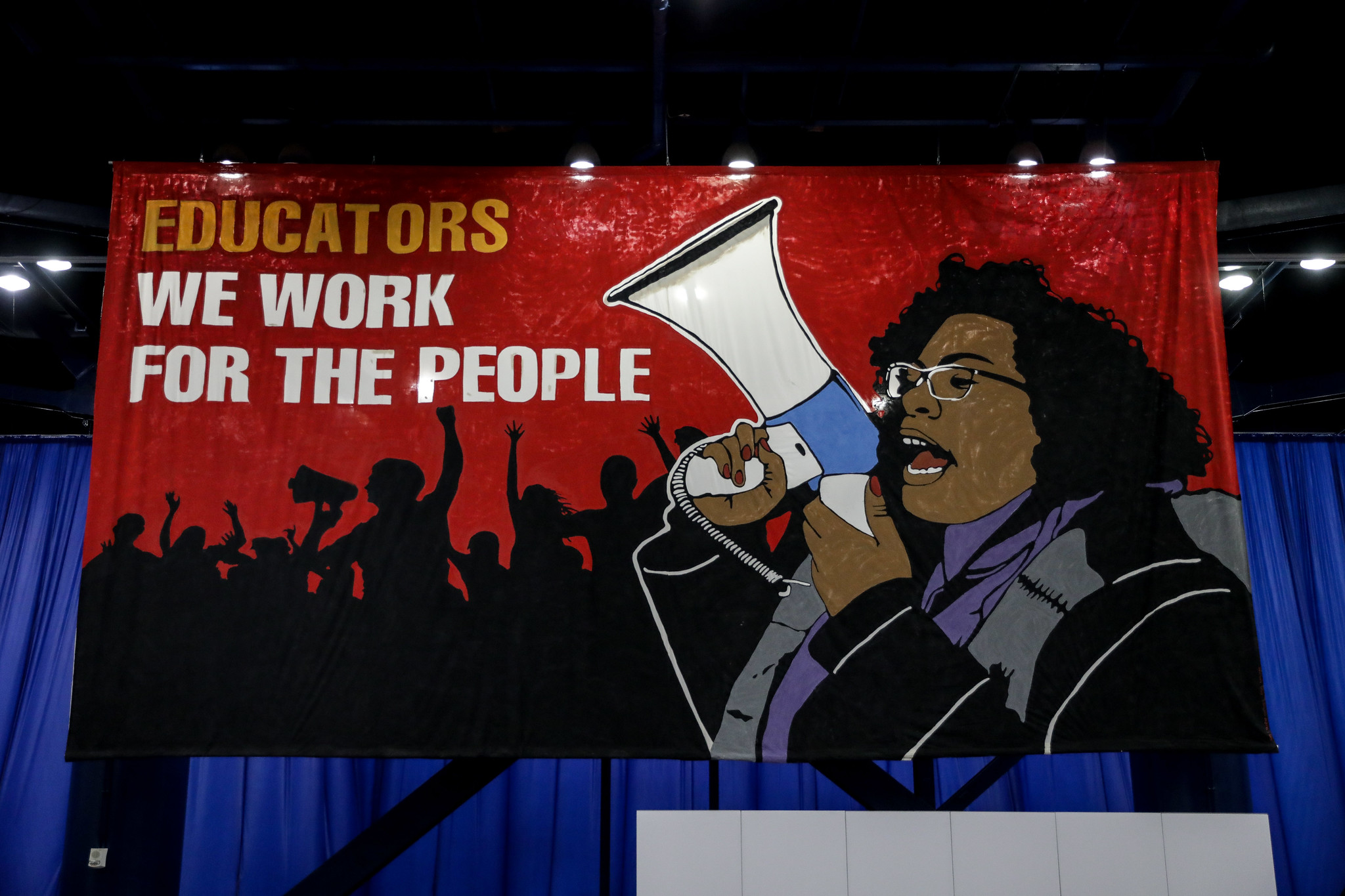

The root of the word assessment is the Latin word assidere, which means "to sit beside." Assessment is quite literally the practice of sitting beside our students as they learn—to guide them, to work with them, to push them, to understand them. Assessment is so much more than what it has been narrowed to: testing, grading, evaluating, judging. Assessment is a partnership and a working together toward learning. So when I design learning tasks, in addition to thinking about my students' interests and strengths and needs, I consider what I might enjoy doing—because often, I will end up doing it alongside my students or as a model of what might be possible. And this is actually one of the great unspoken pleasures of teaching: working alongside your students—creating with them, questioning with them, writing with them.

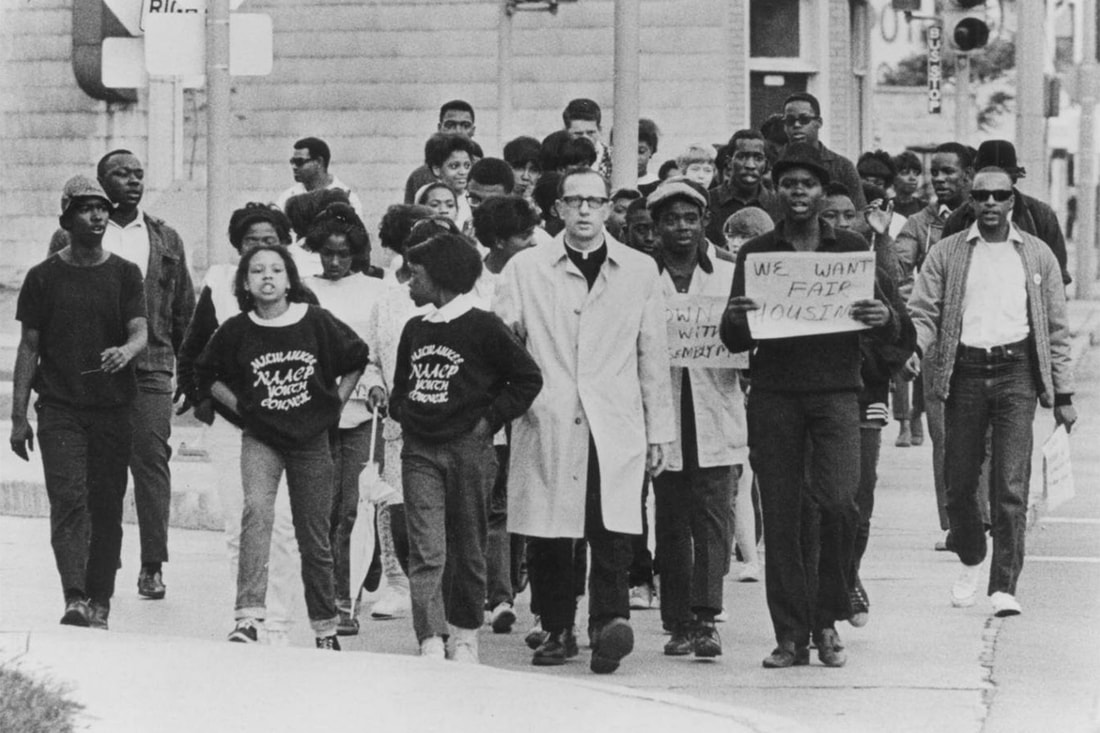

Or, Teaching Milwaukee's Open Housing MarchesLast week, I was forced to admit something: My students want me to lecture. They like it when I stand up and tell them things while they sit back and listen.

That feels sacrilegious to say, but it also feels true. At night the words come

effortlessly long forgotten but now: Je suis Je vais Je peux Though in the red brick streets by day I am stumbling over words and uneven pathways and dead-end mazes I am stumbling. Stand at the corner of 5th and National, and here’s what you see: An antique store, a dance studio, a purple-doored hamburger joint, and a row of Bubblr bikes for rent. The busy intersection is gritty, somewhere between industrial and cool, sort of gentrified but also still unpolished. The rumble of the interstate one block west is a reminder of the neighborhood’s centrality, as are the three rivers that border it.

This is Walker’s Point. It is in fact nothing short of a miracle that the modern methods of instruction have not yet entirely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry; for this delicate little plant, aside from stimulation, stands mainly in need of freedom; without this it goes to wrack and ruin without fail." —Albert Einstein What do you notice when you walk outside in the morning?

Me, I notice how the light is dappled differently through the east-facing trees in September than it is in July. I notice the smell of toasting bread from the corner bakery. I notice that some mornings the grass is heavy with dew. I notice the remnants of a car window smashed into the street. I notice an older woman rushing to the #60 bus and my neighbor languidly walking his dog with coffee in hand. Even in my own frantic race out of the house, I notice. And that noticing usually turns into wondering—sometimes on task (“What exactly is the dew point, again?” and “I wonder whose car got broken into?”), sometimes not (“Why is adult life just one big rush to get everywhere and still always end up late?”). This is just the fabric of my mind’s life: noticing and wondering, wondering and noticing. In other words, I take for granted that I am curious and that curiosity drives my experience of the world. It’s been a while since I’ve felt the first-day butterflies. Whether because I’ve been teaching the same classes over and over, or teaching online, or teaching adults who are a little less nerve-wracking, the first teaching day of a semester has morphed into being just another day of work.

But not last week. It is Day 427 of pandemic life. In those 427 days, my children have attended seven days of school. I have attended zero days of campus-based work. I have spent 48 hours away from them. 418 days of forced, full-time togetherness. 418 days of spontaneous statements of "I love you" and "I hate you." We keep thinking we are in Mile 24 of this marathon, and then the calendar and the days and the exhaustion keep yawning ahead and we realize that, actually, we are still at Mile 15. These have been the strangest, most exhausting 427 days of my life. And this is my lament.

I am tired. At 18, I found myself alone on a plane to Paris. I had about $2000 in tips I’d saved up all summer, a one-night reservation at a Left Bank hotel, and a letter of permission from the French government to apply for seasonal work. I did not have a return ticket to the States.

When I taught middle school social studies, I had a set of questions that I taught to my students to guide how we encountered historical narratives. I called these “The Critical Historian’s Essential Questions” and had them written on a big, handmade poster at the front of the room:

While I taught these questions as a way of engaging students in critical disciplinary thinking (and I’ve written about that as part of my scholarly research here and here), I’ve come to realize that these questions are more than that. These questions are a kind of moral compass, helping to orient us towards voices and perspectives that might be otherwise overlooked. In fact, a few of these questions— Whose perspective does this narrative represent? Whose voice is missing from this narrative? How would this narrative be different if told from another perspective?—have helped me unlearn whiteness, an idea I’m going to come back to in a bit. Suffice it to say when I wrote and taught these questions in my middle school classroom, I didn’t know any of this. I only knew that I had to teach a textbook called The Medieval World & Beyond, and that I knew little about the medieval world but a lot about how to approach curriculum critically (thanks, PhD in Multicultural Education). I also knew that a teacher didn’t have to be an expert in every single fact that they taught, and that it was often more powerful to apprentice students into habits of mind, visible thinking routines, and academic discourse (thanks, Paolo Freire). My students and I could learn the facts together while I modeled what it looked like to encounter those facts as a critical thinker. These “critical essential questions” were how I turned these broad ideas into a concrete instructional practice. If there are any angels in heaven, they’re all nurses.” Picture a nurse. What do you see?

For most of us, we see a woman. Teachers have used this thought experiment for years to teach about gender stereotypes, helping us see how they live inside our own imaginations and then debunking them with stories of “Anyone can be anything they want.” This is an important lesson! I remember, after all, my own shame during a high school history class when I realized I drew only men as doctors and firefighters and scientists and professors. Me, an under-18, card-carrying NOW member! I was guilty of stereotypical thinking, too. For there is always light, if only we're brave enough to see it. If only we're brave enough to be it. —Amanda Gorman, "The Hill We Climb" What is a prayer?

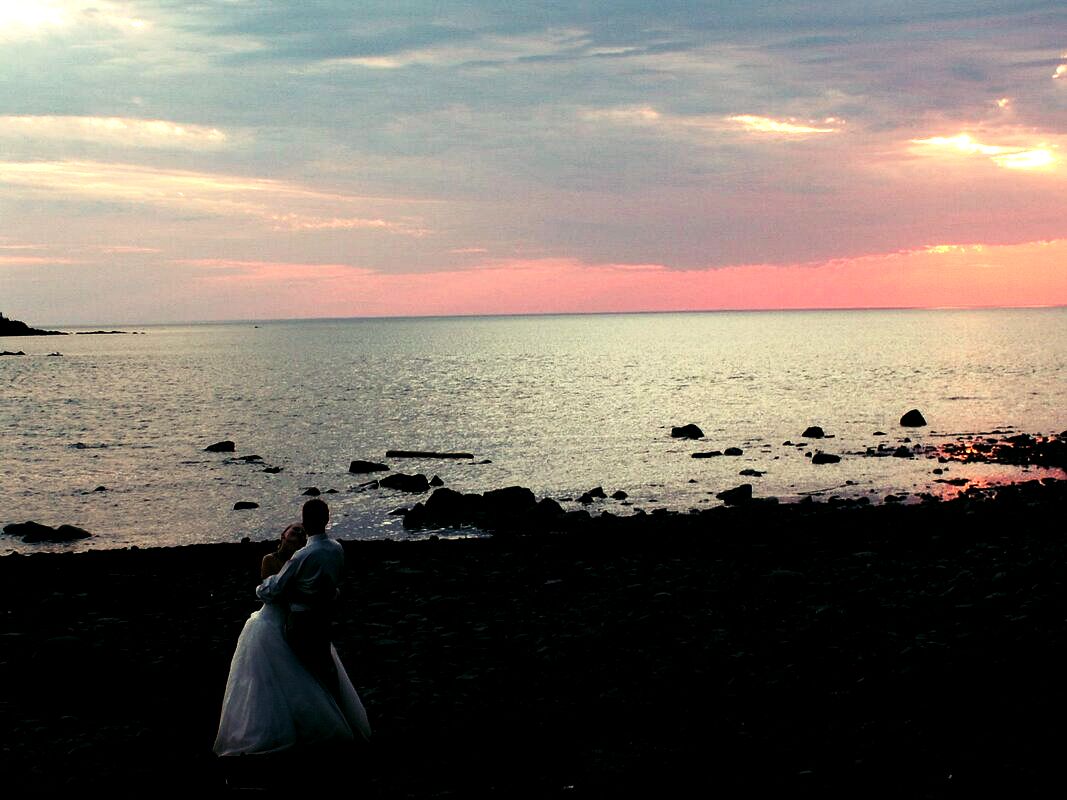

Palms together. Fingers at heart. Eyes closed. Calling out or whispering into the universe for: Help. Love. Guidance. Clarity. Safety. Gratitude. Peace. Desires. Someone must be listening, right? We keep praying, or we stop, but we know that surely this is prayer: Palms together. Hands at heart. Eyes closed. Calling. We were on the shores of Lake Superior when we learned about George Floyd’s murder, just as we were when we learned about Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor’s murders. We were in Eagle Harbor, our home-away-from-home, where generations of my partner’s family have lived and worked and played. We were getting bonus months up north in this very white community thanks to COVID-19 and our stable white-collar jobs that had us working remotely. We had fled north when school closings and shelter-in-place orders were popping up back in March in order to be available for my mother-in-law, who lives alone, but we also knew that, for a while still, we were safer up north, where we joke that social distancing is the way of daily life. And so we were also on the shores of Lake Superior when we began to learn about the disproportionate effects of the pandemic on Black and Brown communities in Milwaukee. As we mourned and raged and talked in that grand kitchen with in-heat flooring while looking out over another lakefront sunset, I was reminded that we were also here when Sylville Smith was shot in 2016 and Sherman Park rose up. And I started jogging my memory to remember, what other explosions of injustice were witnessed from afar, up here in Eagle Harbor?

|

AboutWhile living in Mexico, I joked that speaking Spanish forced me to be far more Zen about life: Since I could only speak in the present tense, I was forced to just live in that present tense. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

photosLike what you see? That's mostly Ross Freshwater. Check out my talented partner-in-life's photo gallery. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed