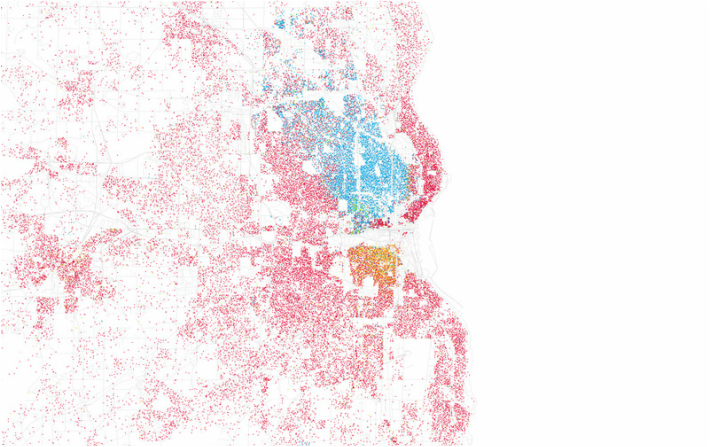

There is a sense in which we are all each other's consequences. | Wallace Stegner. All the Little Live Things. Milwaukee burned while we relaxed in the North Woods. This is the inequality we live with, in our Milwaukee home and also everywhere. The fires, the rage, the sadness, the explosion – it is not mine. Mine is from a distance: while we explain to Anna that no, not everyone has a vacation home, we are also reading the news of a community in crisis just down the road from our 'regular life' home. We are heartbroken for our neighbors but also unaffected and wrapped in security systems. We can explain to our neighbors up north, mostly white and mostly well off, that no, the people screaming out are not the judgments being thrown at them and that they are our neighbors. We can explain that Milwaukee, our home, is the fourth poorest city in the US and also one of its most segregated and violent cities. We can tell them that Milwaukee is statistically one of the worst places in the US to be Black. But we can also reassure them that, even though our house sits on the corner of Auer Avenue, our Auer is four miles away from that other Auer, the one that is burning. We can read about Milwaukee’s eviction crisis and its unresolved civil rights history and the politics of school take-overs while we securely live in a home, bought with the help of family members, in the neighborhood of our choosing, with access to a variety of excellent schools for our two precocious, privileged children. We can go to our office and write screeds against the glaring inequality in our community and we can design courses and research that are in some way inspired by our own disgust and moral indignance. We can observe it and talk about it and protest it and vote against it, but we don’t have to live it. We don’t have to live it. And yet, my life is so deeply entwined with the lives of those that do—the lives of those who do have to live the rage and inequality and heartbreak and frustration and persistence and resilience. And I don’t mean on a philosophical level, like the we-are-all-oppressed-by-oppression platitudes. I mean it on a material, concrete level. That money that I get back on my tax return for being a homeowner? That could have been someone's rent voucher. My call to the police department because someone was driving 80 on my street, or because our lawn mower got stolen, or because a neighbor got mugged? That means more policing in District 5, a district that can’t really stomach any more policing. The city amenities we enjoy – the parks, the concerts, the repaved streets, the super convenient bus line that runs right in front of our house, the beaches, the beautiful libraries, the recreation program – these are all subsidized by what we as a community have decided not to spend our money on: schools, child care, affordable housing, jobs programs, mental health services, domestic violence support. Whether I want to see it or not, my life is entwined with those of a community rising up against the lives they are cornered into leading. And I suppose that I justify these things, guiltily whispered to myself. What incentive is there to buy a home in Milwaukee without a tax break? Home ownership is good for the economy and the city and the neighborhoods and the schools, right? Of course tax breaks are a smart investment! And I have a right to live in a safe neighborhood free from violence and theft, where I can walk alone without worry. And those city and county amenities – man, can you imagine if we had to pay full price for them? If I had to pay a couple hundred dollars for swimming lessons instead of $35? Then how would I afford the children’s choir? Or summer camp? Or vacation up north? I justify these trade-offs because they benefit me and because I feel entitled to them. And that’s the thing. Most of us who live with privilege, we feel entitled. Not even in the outrageously out-of-touch bootstrap way but because we have lived with our privilege for so long that to live without it, to give up even just a little bit of it, feels like we are being punished, like we are undeservedly having what is ours taken from us, like we are making a sacrifice that we shouldn’t have to make. But the flip side? Someone else will have to make a sacrifice. And that someone else is likely to be someone who has already sacrificed far too much: housing, food, quality schools, health care, jobs, political power. And also dignity, safety, hope, equity, justice. So tell me: who should be making the sacrifice? In my work with educators, I am always explaining that we teach in an unjust and racist system. An education designed to reproduce inequity and privilege and social hierarchies. We cannot divorce our own personal good intentions from this history into which we step and from which we come. A history of segregation, cultural extermination, class calcification. A history of eugenics and exclusion and neglect. A history that has fed into the school-to-prison pipeline, achievement gaps, school privatization, the standardization of everything. Whatever our own good intentions and whatever our own positive experiences with schools, education in the US is a systemically racist and structurally unequal system. So what are we going to do? And it’s not just schools. We know all too well that this is true of our systems of policing, housing, policy making; of economics, politics, laws. Whatever our own intentions may be, these systems are not designed to reflect those intentions. So what are we going to do? When I say this, I am usually met with a defensive, “So are you saying that I’m a RACIST? Because I’m NOT a racist.” Or, “So are you saying that all teachers/police/politicians/judges/citizens are RACIST? Because they are NOT all racists. My brother/sister/friend/mother/father/husband is a [insert career here] and they are NOT racist.” So let me be clear: I’m not saying that you are intentionally racist. What I am saying is that if we ignore the systems in which we are embedded, we make them stronger. We end up supporting them. When we wrap ourselves in the shield of personal intentions and individual examples and defensive justifications, we ignore the miasma of injustice in which we exist. And when we ignore it, we acquiesce to it. We become part of it, whether we meant to or not. Our silence, our business-as-usual, our unwillingness to see hard truths: It’s an acceptance of the status quo. It’s the acceptance of a system in which, while I lazed away my mid-August weekend looking for Northern Lights, my city back home smoldered with sadness. And those two things are connected, no matter how hard any of us may try to pretend that they’re not. Driving home from soccer camp one day in July, my daughter looked out our mini-van windows at the suburb rolling by. Tree lined. Neat lawns. Skinny moms with lattes. Kids learning to ride bikes. Crossing guards. Retirees tending flower beds. Slow moving traffic. Badminton nets in yards. Flowered medians on quiet streets. She looked out the window and sighed, “It’s so pretty here. I wish we lived here.”

I was taken aback. “But our neighborhood is pretty, don’t you think? Our boulevard has all those beautiful trees and big old houses and our neighbor has a rain garden and…” I trailed off. She was shaking her head at me: "No, it's not pretty like this." And I knew she wasn't really talking about it being pretty. This place is easy. Wrapped discretely in privilege and sameness, it just feels easy. Idyllic. But there’s a moral cost to that ease, and that’s not the morality that I want my children to grow up with. So we live in Milwaukee, in a part of the city where our neighbors are all sorts of everything. Our kids go to a school where there are children of professors and children who live in housing projects, and they're friends, and where none of my children's teachers this year were white. We get our shoes cobbled in a local shop on the North Side where the owner pulls loitering teens off the street to polish away. We drive down streets we’ve been told are too dangerous for us with our windows down—because that’s the way to everywhere else from our neighborhood. We live in a district represented mostly by people of color. We go to the city’s public pools and public beaches and public parks, where for a moment, you can forget that this is one of the most segregated cities in America. If you're white in Milwaukee and if you're well off in Milwaukee, this is not the norm. You have to seek it out. And so, even though we do it imperfectly, we keep seeking out places to come together as neighbors, across race and class and language. Across fear, too--because it can be scary to actually face the tangled knot of our co-existence. So I get it, kid. I know that the lush, quiet suburb with the mall that looks like a small town and the quaint movie theatre where kids walk all by themselves and where there’s a park on every corner and an ice cream truck in summer, I know that its ease is tempting. But I also know that its ease comes at the expense of someone else’s hardship, and when you stay wrapped in the cloak of comforting sameness, it’s too easy to pretend that this connection doesn’t exist. It’s too easy to pretend that the fires in Sherman Park are about someone else’s city, someone else’s failings, someone else’s misery. But that’s just not true. We live in Milwaukee. Gritty and imperfect and violent and beautiful and lively and diverse Milwaukee. If our lives are connected, let it be visible: house-to-house, shoulder-to-shoulder, me pushing your kid on the swings and you pushing mine. Because the only way our communities will ever see justice is if we, in the words of Bryan Stevenson, get “proximate” to one another, if we learn to respect all the imperfect humanity in our neighbors – and ourselves. And then hopefully, through all our imperfections and connections and conflicts and fears, from the uncomfortable head nods and the small talk at the dog park to block parties and playdates, we can together make a community that is just as beautiful as that leafy suburb, not because of its trees but because of its dignity and justice and Ubuntu. I get it, kid. I too feel the lure of hiding from the inequality all around us, of trying to forget the costs of our own luxuries. I really do. But this is also the crux of privilege: being able to think of those Milwaukee fires as someone else’s problem, with miles and worlds between us as we tuck ourselves away in the safe place, the easy place. But, my dear child, easy is not the same thing as right.

2 Comments

Jill

8/19/2016 09:42:30 am

Insightful,profound truths that guide/ stimulate personal reflection.Thank you.

Reply

Stephanie Wakeman

8/19/2016 04:33:56 pm

Melissa,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AboutWhile living in Mexico, I joked that speaking Spanish forced me to be far more Zen about life: Since I could only speak in the present tense, I was forced to just live in that present tense. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

photosLike what you see? That's mostly Ross Freshwater. Check out my talented partner-in-life's photo gallery. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed