|

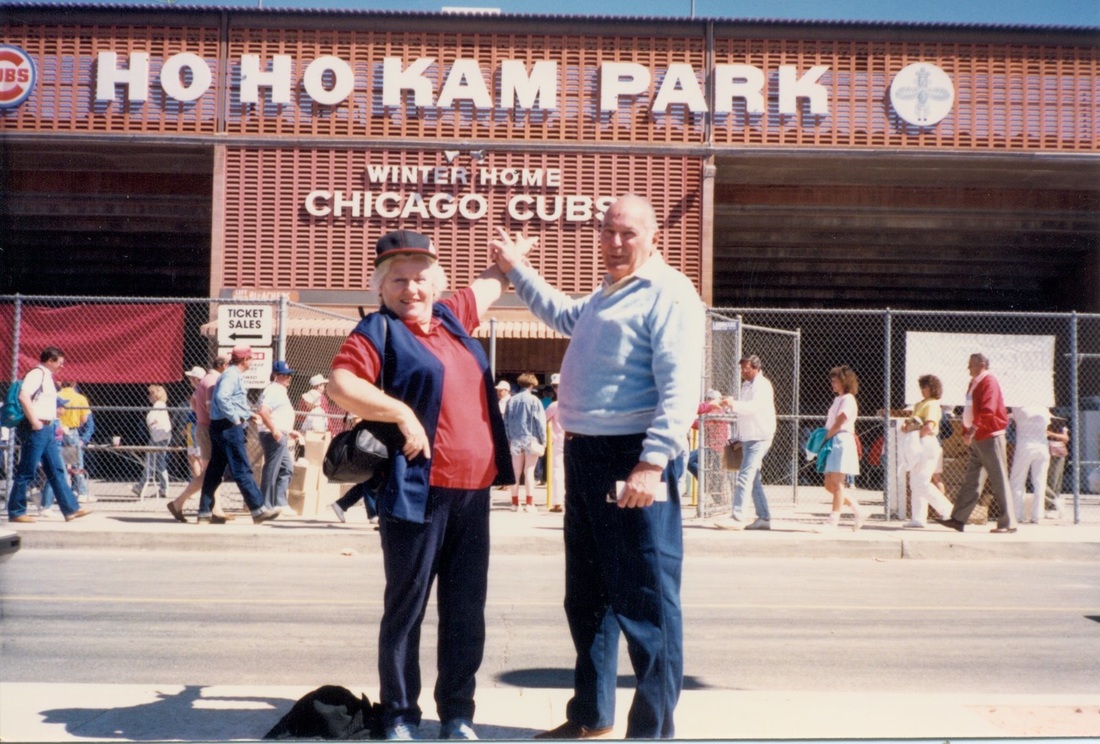

In my Chicago family, spring was ushered in by a pilgrimage. On a cold, early spring morning, our mothers called us in sick to school. In early gray hours, we’d bundle up, in red-and-blue caps and layers of hopeful spring clothes, and make our way into the city. The first destination: the McDonald’s parking lot at Clark and Addison, where an extended clan would gather. While the moms sorted through snacks and layers and blankets in the back of someone’s wood-paneled station wagon, the cousins and I skipped around the parking lot, singing, “Take me out to the ball game…,” dreaming of peanuts and malt cups. Then someone would give the orders, and off we were, across the street to where that red sign welcomed us to the Wrigley Field home opener. Decades later, a trip to Wrigley Field is no less monumental for me. My Cincinnati-raised partner, however, can’t understand the obsession. “It’s nothing but a bunch of drunk, Lincoln Park yuppies and their stock broker boyfriends. At least with the White Sox,” he boasts, a converted devotee of the South Side grinders from before they won the World Series, “you hear ACDC at least twice, and every working man in the city is keeping track of the stats on his own scorecard.” I’ll concede: Wrigleyville has become a drunken wasteland, where the twentysomethings are more interested in who they’ll hook up with than Lou Piniella’s managing magic. The ancient den of the Swedish American Club, where my family would gather on so many game days, has long been converted to the Improv Olympic, and the Cubby Bear attracts more freshly minted Big 10 grads than the working class crowd that hung out there a generation ago. And since this is the only Wrigleyville that Fresh has ever known, I can forgive him. But what he doesn’t understand—and what the generation of young Chicagoans about to cheer on the Cubs in their postseason berth don’t understand, either—is that it hasn’t always been this way. Despite Wrigley Field’s having grown into the world’s largest outdoor bar, it is still hallowed baseball ground, especially for families like mine. My grandfather grew up down the street from Wrigley Field during the Great Depression. As he shuttled from boarding house to boarding house with his younger sister in tow, his parents evaded their responsibilities in neighborhood bars. I can only imagine what the fabled baseball team just around the corner meant to him. That 1908 World Series championship was still fresh in the city’s memory. This was a great ball club, and to a boy trying to find his way in the world, it offered hope. My grandfather, Vern, spent his childhood within earshot of the park and mimicking the greats inside of it in the ball lots of his childhood. He played youth ball with the first Boys’ Club in Chicago, on Addison, and later went on to star on Lane Tech’s baseball team. While his parents had offered him little in the way of support or direction, the Cubs’ example made up for it. After high school, Grandpa tried to give his life to baseball. He spent his early twenties traveling around the country playing not for the Cubs but their South Side rivals, the White Sox, showing up in Mobile and Peoria and hoping they needed him that day to play a farm team game--and hoping, after that, he’d finally make the big time, and eventually play in Wrigley Field. He never did. World War II came, his girlfriend became his wife, and his Major League future disappeared. Alas, the Cubs mirrored these lost hopes. In 1945, they made it to the World Series again, only to lose. This must’ve been particularly heartbreaking for my grandpa, who felt shamed by baseball during the war. Because of his baseball prowess, the military kept him stateside as a “morale booster,” fixing planes in New Haven and touring Army bases to play baseball rather than fighting on the front lines. He had lost a brother-in-law at Normandy and friends across the Pacific, but he’d never been in harm’s way himself. He was embarrassed by this sheltered wartime status. Never mind that his friends who’d fought tried to explain just how important he and the other “morale boosters” were to their efforts. He’d been both saved and embarrassed by baseball, and with this bittersweet service record fresh on his mind, he was let down by baseball again with that 1945 World Series loss. People like to joke that loving the Cubs is the ultimate act of masochism, and maybe it is. Despite his personal and National League disappointments, Grandpa’s love of baseball and those cursed Cubs got passed onto his progeny. His unrequited love became my own right of passage. As a kid growing up in the suburbs with a family rooted in the North Side, I looked forward to our pilgrimages to the Friendly Confines, to the malt cups I ate with chattering teeth and to Harry Caray’s voice, and then to the post-game drive through the old neighborhood, past the family house on Berteau, my mom and her siblings reminiscing about their childhood. I marked the passing of each summer by days spent on Grandpa’s knee, an Old Style in his right hand, watching the Cubs on Channel 9. We’d sit together silently for most of the game, interrupted only by the occasional grumble from Grandpa about Don Zimmer’s managing and by the chorus of the seventh-inning stretch.

By the 1990s, my grandparents had retired out to the country and our baseball watching was no longer shared in time and space. But my cousin and uncle owned a restaurant across the street from Wrigley, and they’d ply me with standing-room-only tickets. Leaning against the railing in the Upper Deck all by myself, I’d laze away the afternoon, just as happy as I’d been on those spring mornings of my childhood. The older I got, the harder it often became to talk with my grandpa. Generations apart and existing in totally different worlds, our lives had diverged. And so every time I visited or called, I’d hopefully initiate a conversation with the one thing I knew we’d always share: “What do you think, Grandpa? Is this the year? Are the Cubs gonna do it?” He’d guffaw, take a swig of beer, and mutter some insult at the team he’d devotedly followed since a boy. But the veneer of cynicism was just that: a veneer. Deep down, he desperately wanted his team to win. We all did. In 2003, in my twenties and finally living within my beloved city, I called him from the corner of Addison and Clark, just after the Cubs beat the Braves: “They’re gonna do it, Papa! This is it! This is the year they’re going all the way!” He laughed and answered wryly, “We’ll see, Brat. Probably not gonna happen in my lifetime.” He was, unfortunately, right. In spring 2005, my grandpa passed away. He never did see the Cubs make it all the way, thanks to that fatal catch in the Marlins series. And as the Cubs’ record continued to plummet in the years since that near-triumph, I’ve worried that I won’t get to see them go all the way in my lifetime, either. But you’ve done it, Cubs: you’ve clinched the division and given us yet one more chance to celebrate. This time, you’ve got to do it. For Vern and for his lifetime of skeptical devotion, passed on to his offspring—and inevitably, to be passed on to our own—you’ve got to do it. For the hundreds of thousands of fans who have come to Wrigley Field, rain, snow or shine, win or lose, generations on. Even for the Lincoln Park girls and their stockbroker boyfriends. You’ve got to do it. This must be the year.

1 Comment

Melissa, thank you for this charming and descriptive window into your childhood family and love of the Cubbies! Your in-laws are so happy that you could be part of the Cubs' victory celebration!

11/6/2016 12:50:19 pm

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AboutWhile living in Mexico, I joked that speaking Spanish forced me to be far more Zen about life: Since I could only speak in the present tense, I was forced to just live in that present tense. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

photosLike what you see? That's mostly Ross Freshwater. Check out my talented partner-in-life's photo gallery. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed